Nigel Jarrett catches Swansea City Opera on tour with a lively production of a now-controversial Mozart opera, Cosi fan tutte, which has been transplanted to 19th century India.

More than whimsy may have encouraged director Brendan Wheatley to set his production of Mozart’s Cosi fan tutte for Swansea City Opera at the time of the British Raj. Despite its sublime music, the comedy has at its core some assumptions concerning human intercourse: namely, the belief that women temporarily beyond the watch of their menfolk will throw fidelity to the winds when prey to the amorous attentions of others (in Lorenzo da Ponte’s libretto, their swains improbably disguised). Today, this is political-incorrectness of high order.

Wheatley knows that the British on the sub-continent were placed as social beings in an environment they did not understand and often did not wish to understand. The truth of this is embodied in E.M.Forster’s novel A Passage to India, where their discomfiture extends, as only Forster could have mapped it, to the frisson of mutually-attracted racial opposites. But that extremity aside, updating from 18th-century Naples provides Wheatley and his team with other opportunities: for creating dashing soldier costumes; for invoking the exotic, in which decamped women might feel both thrilled and vulnerable; and for adding mystery, whereby the figure of Don Alfonso, in da Ponte’s story the mischievous bachelor who sets everything up, becomes a sort of philosophical master of ceremonies – Eastern philosophy, of course, and a cynical practitioner.

The story applied universally would be regarded today as outrageous. Certain it is that suspicions of what men would get up to in their women’s absence would be more justified by a feminist-dominated argument; but objection should work both ways. Temporal shift may thus be the least of an opera director’s considerations in Cosi fan tutte. Although an opera buffa, it prompted Mozart to explore depth of character at odds with its nominal frippery; but that was Mozart’s strength: a sense of fun just about obscuring the deadly serious, even the tragic, in its depiction of the treatment of women by men.

Wheatley scores in the tightness of the ensembles and the concentration on what is musically important: the almost pantomimic antics – their potential milked but not to excess – and the delivery of music so ravishing that it almost floats away from the comedy into a celestial sphere of its own. Only spirited acting by Mari Wyn Williams (Fiordiligi), Aurelija Stasiulytė (Dorabella), Ian Beadle (Guglielmo), July Zuma (Ferrando), Håkan Vramsmo (Alfonso), and Jessica Robinson (Despina) keeps it on board as the action steams along with the unobtrusive support of musical director and conductor John Beswick and his eight-piece orchestra. Most of the arias and multi-voice set-pieces are given their due as pointers to differences in stature between the two female leads, to the equanimity of their self-cuckolded men, and to the willingness of the sparky (and opportunist) Despina and Alfonso to engage in misbehaviour just for the hell of it.

Throughout, and as a result of telling portrayals, one realises how complex the inter-relationships are in a work one might dismiss as irrelevant in an age of at least theoretical equality of the sexes. In its day the story must have been a diversion; now, the downstage and full-frontal celebration by Alfonso, Ferrando and Guglielmo of the ‘truth’ of distaff unfaithfulness is patently a joke and, moreover, an offensive act that makes them look slightly goofy. South African Zuma took over at this performance from Damien Noyce, his understudy, and will sing Ferrando at the remaining stops on the tour. He was originally cast in the role but encountered visa problems in getting to Britain. A slight imbalance in the vocal effectiveness of the cast has to be noted, and a little more could be made of the character drawing.

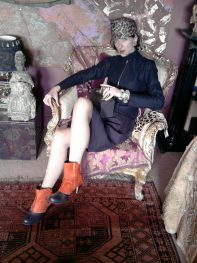

The scene of Wheatley’s interpretation is set in the early part of the 19th-century, but Crown rule of India began in 1858 and ended in 1947. The soldier-protagonists’ uniforms seem a bit out of kilter with history. Fiordiligi and Dorabella are dressed straight out of Jane Austen, who died aged forty in 1817. Don Alfonso wears a head-dress so is half-mystic, and presumably Indian, though his attire also seems to belong to an earlier era. Wheatley retains da Ponte’s original names, which seems odd: the Italians had no stake in Raj India. He does raise the topic of miscegenation in having Ferrando and Guglielmo disguised as Indian princes, and the final mock wedding ceremony of the men and their ‘unfaithful’ women is therefore bold.

The production is revived from 2012, with the same design (Gabriella Ingram), the same English translation (Ruth and Thomas Martin), a completely different cast, and a community chorus which might have been directed on this occasion to better effect, though as witnesses upstage to such horrid schadenfreude it was perhaps justified in appearing slightly stunned and half-hearted. In the meantime, and before that, the company in a former guise has put on a series of operas tailored to reduction of both music and means; in other words, to theatres far removed from anything resembling opera houses. It’s a skill, and its drawbacks have to be allowed for and tolerated. Not that all ‘chamber’ versions of opera successfully exploit every advantage and avoid every pitfall. The minimalist set here was sufficient unto the needs thereof, and softly lit, which left the cast to get on with it; and they did, to no mean satisfaction.